Battle of Hayes Pond

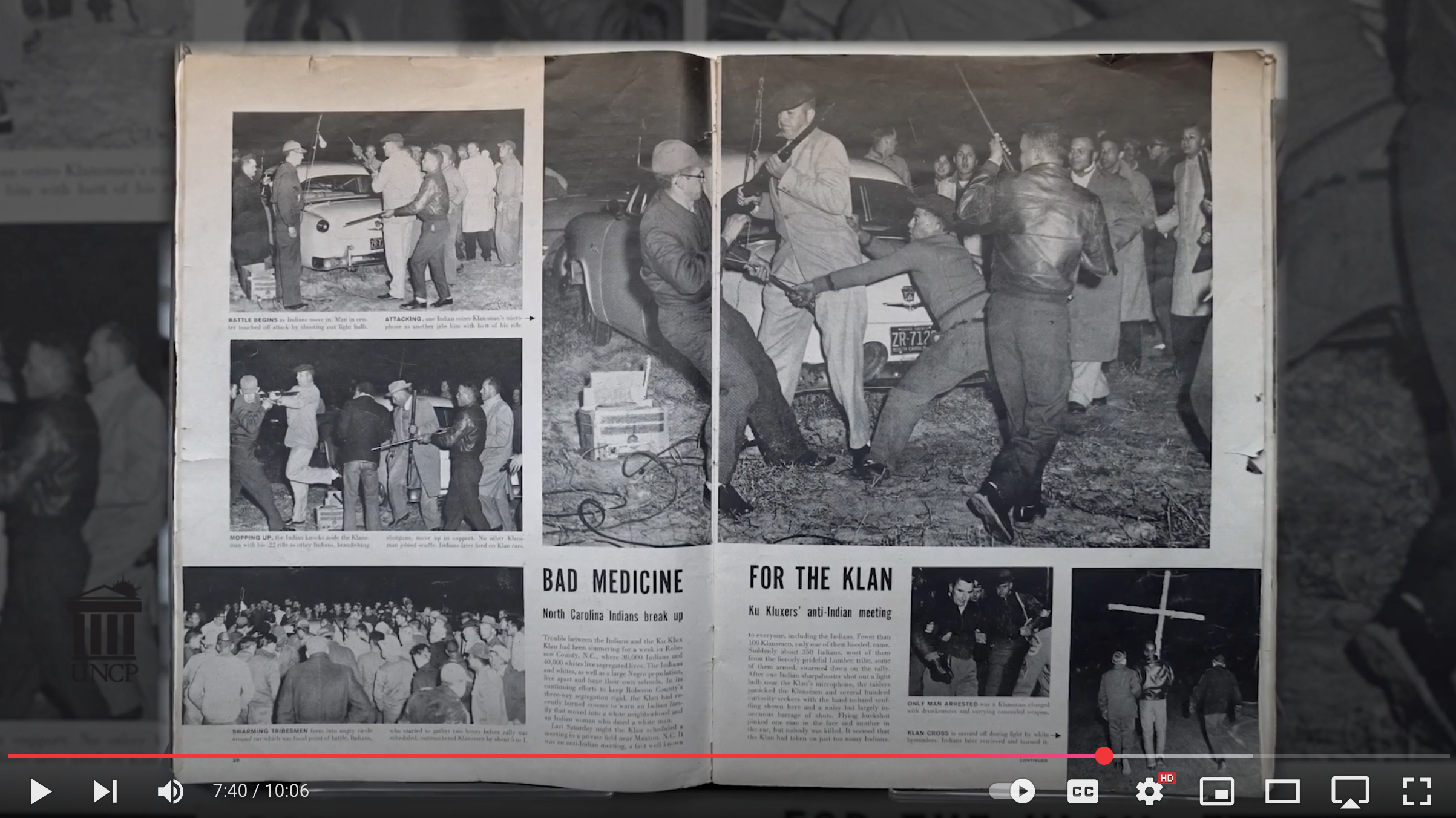

The confrontation at Hayes Pond made national headlines. LIFE magazine published two stories on the event. Letters of support for the Lumbee flooded into Robeson County from across the United States. While the Klan wasn't defeated permanently that night, it got the message loud and clear: they were not welcome in Indian Country.

This powerful example of Indigenous and community resistance lives on as a symbol of strength, dignity, and solidarity in the face of hate.

Play Video

Play Video

Play Video

Play Video

Play Video

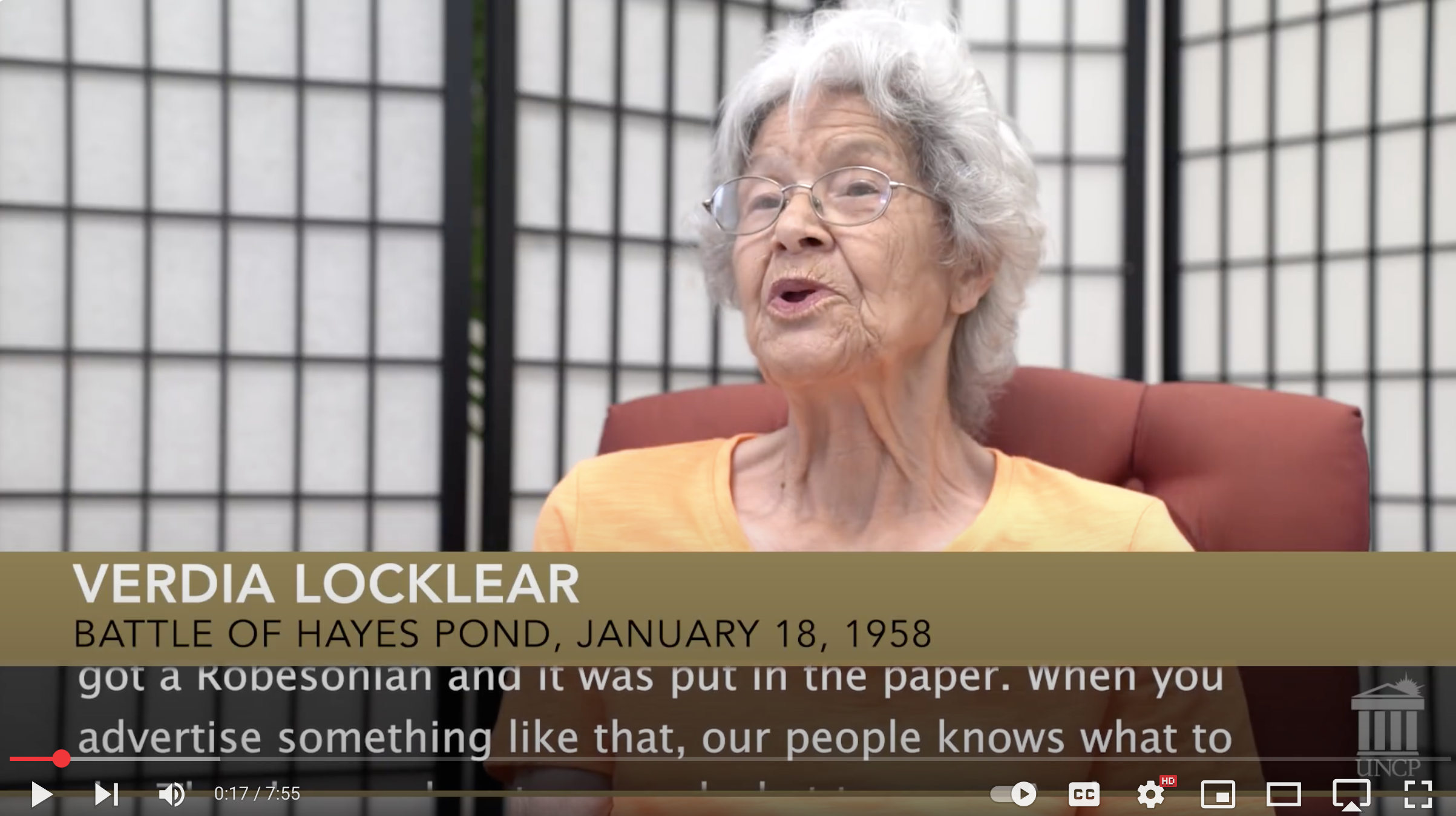

Play VideoBattle of Hayes Pond: The Night the Klan Was Routed

On the night of January 18, 1958, the Ku Klux Klan planned to hold a rally in a field near Maxton, North Carolina. The event had been publicized for weeks, sparking tension and concern across Robeson County.

Maxton Police Chief Bob Fisher — who also served as Mayor — had written to multiple law enforcement agencies, including the State Police and FBI, requesting their presence to prevent what he feared would become a violent confrontation. He made his position clear: he opposed the Klan and did not support the rally. Despite his efforts, the event was set to proceed.

Meanwhile, members of the Lumbee Indian and Black communities grew increasingly alarmed by the Klan's recent cross-burnings in nearby towns like St. Pauls. The rally represented a direct threat to their safety and dignity. Many community members, especially women, urged their loved ones to stay home. But the Klan had gone too far.

That night, an estimated 500 to 1,000 Lumbee men — many armed — gathered to confront the Klan. As they approached the rally site, reports suggest Black residents also offered support if needed. Ultimately, the Lumbee acted decisively on their own.

As the Klansmen attempted to begin their rally, they were quickly surrounded. Heated words were exchanged. Shots were fired into the air. A single light bulb illuminating the field was shot out, plunging the area into darkness. In the chaos, the Klansmen fled — leaving behind their flags, their burning cross, and their rally materials.

What could have been a tragedy became a remarkable moment of resistance. No one was killed, and only minor injuries were reported.

Most of the materials for this permanent display were generously donated by Mayor Bob Fisher.